Friday, April 27, 2012

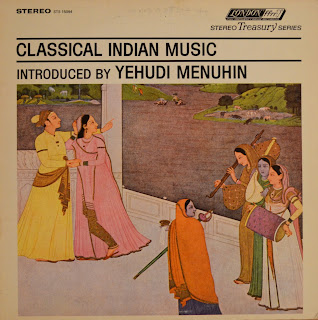

K.S. Narayanaswami, Narayana Menon, Palghat Raghu: Classical Indian Music introduced by Yehudi Menuhin, 1963

Today's pick is ethereal, with the two Narayanas on vina and Raghu on mridangam, but this is not your typical Carnatic record. The album is supposed to be an introduction to Indian music for Western listeners, literally presented by Yehudi Menuhin who gives a spoken explanation of the music and quick summaries of the musical structures of each song. His speech covers the history and components of Indian music and includes a fair bit of praise for the tradition.

Menuhin is an interesting musical figure: he is an accomplished concert violinist considered by many to be among the best of the 20th century and was born into a prominent rabbinical line as the son of Eastern European immigrants in New York. According to wikipedia, he gave a concert with the Berlin Philharmonic two years after the end of the holocaust as a gesture of reconciliation, (he was the first Jew to do so,) and defended himself by saying that the conductor Wilhelm Furtwangler had never joined the Nazi party and had helped Jewish musicians. He apparently also went beyond the bounds of Israels' comfort zone by performing benefit concerts for both Israelis and Arabs in the wake of the 6 Day War. Menuhin's controversial and at times activist use of classical music was motivated by a belief that nationalism and the global complex of competing governments inhibits peaceful coexistence. Along these lines, the Encyclopedia of World Biography credits him with a strong role in encouraging a cultural exchange between the US and USSR in 1955. With an eye to the international, it's no wonder that he was drawn to Indian music. Interestingly, some of his early exposures to Indian culture were not strictly musical but also through yoga.

Of Indian music in general, Menuhin suggests that performances are not finite because the beginnings and ends of songs are lost in the past and future as the music flows from tradition as from a river. He opposes it to Western music, which he says develops through a series of "actions and reactions," often expressions of present social circumstances more than a respect for past work. He stresses that before the advent of recording technologies, the music was transmitted exclusively through the didactic relationship between student and teacher. This history of Indian classical music follows a very typical narrative about the music's continuity. Menuhin's presentation (especially the hype at the beginning of the speech) gives the impression that this record contains a prime example of the kind of studied traditions that he describes, and the music delivers. This narrative is particularly interesting in the context of this record, because Narayana Menon was the Deputy Director General of All India Radio, Delhi, at the time of this recording. (He is credited simply as the All India Radio director in Peter Lavezzoli's The Dawn of Indian Music in the West: Bhairavi, and he apparently also held high posts at a number of other official music organizations.) Menon must be a fascinating figure in his own rite: he has published books on music, dance, and the poetry of William Butler Yeats, whose work he studied intensely in his pursuit of a poetry doctorate at Edinburgh University. And it was Menon who introduced Menuhin to Ravi Shankar, beginning a friendship that spawned multiple albums.

Menon's appearance on this record of exemplary Indian music got me thinking about his place in the world of Indian music. He presumably had a rare level of control over the shape of Indian music, because in addition to defining the music by playing it masterfully, he had some influence over what kind of music was recorded, broadcast, and sold. As I say in a previous post, I have heard that many musicians abandoned their resistance to the harmonium as an accompaniment instrument after All India Radio agreed to include it in recordings. I wonder how strongly music is guided in certain directions when a group of individuals, whose tastes are ultimately subjective, decide what music is fit for circulation.

Although Indian music emerges from a long, deep, and powerfully expressive tradition, it actually exists in the minds and practices of individuals who define it in their own ways, and these individuals learn from individuals within the stylized framework of a gharana. While the music might flow from tradition, it is difficult not to read that tradition as an interconnected web of similar but separate practices rather than a single stream. The general differences between Hindustani and Carnatic styles not to mention the variations from gharana to gharana would seem to indicate that there is no ultimate form of Indian music, that artists with carefully crafted sets of musical tools pursue musical and often spiritual depth with rare technical virtuosity. And while the commentary on the record and the jacket avoid the pitfall of calling this music an expression of the purest Indian music, one has to imagine that this recording falls comfortably within the official, standard vision of Indian music. When Menuhin implies that millenia of tradition led to the creation of this very record, other visions of Indian classical music with less official recognition get edged out.

The truth is that some gharanas not only look down on other gharanas, some don't even recognize others as true practitioners of raga. And where does such a subjective system for determining legitimacy leave musicians like Lacchu Maharaj, who does not fit exactly into any one gharana but appropriates elements from many? As far as I can tell, there is no universal judge of true raga, but organizations like All India Radio have nudged public opinion in one direction or another by crystallizing certain styles into monuments of culture in the process of transforming them into recordings. But to avoid sounding too critical, let me close by reiterating how masterful and serene the music on this recording is.

Thursday, April 19, 2012

U-Roy: African Roots, 1976

This album seems to be a compilation of music from at least two sources. The A side is all U-Roy cuts, some of which are undoubtedly avaliable on other blogs, and the B side is all instrumental cuts from King Tubby's studio. I thought I would post this album to share the cover art and because the opening song, Joyful Locks, is so classic. Like most (or all?) of U-Roy's songs, it's a remix. He sings over Linval Thompson's "Don't Cut Off Your Dreadlocks" rhythm with some of the original vocals dubbed back in. U-Roy's version preserves both the theme of Thompson's song and the spirit of the lyrics that he drops in his rendition. For example, even though he omits the warning, "(don't you cut off your dreadlocks) because Jah Jah will chastise you, even hurt you," he keeps Thompson's reference to the story of Samson and Delilah, a parable that some Rastafarians deploy to emphasize the importance of hair as a significant component of one's relationship with the divine. And although he drops the line about men with dreadlocks being righteous in spite of their reputations as evil, he does say, "don't look back, and don't don't you cut off your dreadlocks," and "got to be truthful most of all to Jah." In other words, having committed himself to God, a Rastafarian should concern him or herself primarily with the divine relationship; all other relationships should be secondary, and the people who scoff at the Rastafarian's path should be of no concern. As U-Roy says, "let Jah arise and all his enemies be scattered away."

In this light, the story of Samson and Delilah takes on a new relevance: Delilah stands in for the people and institutions that make up Babylon, the blanket term for all that is spiritually maladjusted and/ or motivated by greed. The Rastafarian must treasure his or her locks, through which the divine relationship is realized, but must also protect this relationship because his or her devotion and purity of heart are under constant siege by Babylon. As Johnson says in both versions, "Samson was a dreadlocks so Delilah betrayed." In other words, the evil that confronts Rastafarians' is not strictly the collateral damage of being poor and marginalized in the modern world. The evil inherent in Babylon motivates Babylonian subjects to consciously interfere with the Rasta's quest to abstain from all that is impure. Jamaican police (and police around the world) consider the Rastafarian evil or dangerous because they define marijuana, the Rastafarian's sacrament, as evil, and many members of society at large, especially the wealthy, reject the Rastafarian notion that greed and inequality are inextricable from Western society. Some try to persecute those who blame the unequal distribution of wealth and power on a culture of greed, and Rastas take this doctrine further than most. Rastafarians allege, reminiscent of the teachings of Christ, that spiritual purity overwhelmingly tends to be mutually exclusive with the ambition necessary for the accrual of wealth; there is simply not enough room in one soul and one lifetime for these disparate traits to coexist without one eclipsing the other. Babylon is a cultural atmosphere that favors the ambitious, and it defensively attacks those who criticize it and try to escape it.

This song encapsulates the kind of appeal that reggae, loved by musicians across an unusually wide spectrum of ethnicities, has to enthusiasts worldwide. In places like New Guinea, where capital and sovereignty elude so many indigenous people and power is the privilege of a small, mostly stagnant elite as well as foreign capital, reggae was adopted and endowed with local meaning. The same is true in so many Native American communities, many of which have achieved legal sovereignty but still struggle against poverty, marginalization, and discrimination. The music also has a surprisingly long history in various corners of the Arab world, whose people have for over a year been toppling despotic rulers. For most non-Jamaican communities of listeners (except for those in Black Africa and the African diaspora,) it is not the Africanist-Abrahamic God called Jah that draws people to the music, but rather the way reggae recognizes the torment that people face when walking a difficult but righteous path. I genuinely believe that it is the emphasis on living a righteous life in an evil world and the analogy between different kinds of oppression that makes reggae a global language, not the ubiquity of marijuana in the lyrics that arguably accounts for reggae's popularity among most Anglo-American listeners.

This song in particular can speak to just about anyone on the grounds that it can be difficult, even scary sticking to one's convictions, but without the strength to do that, we are truly powerless, just as Samson was when he allowed the holy relationship to which he had devoted himself to be severed along with his hair. It's true that God returned his powers to him one final time so that he could bring down the temple on his captors, but he died in the process and his old life was never restored. The message is that when it comes to sticking to one's beliefs in the face of adversity, the stakes are high and if we falter we may never regain our footing. It's a message that can resonate as easily with a Jamaican Rasta as a New Guinean in danger of losing his or her ancestral lands permanently to Chinese lumber interests.

Wednesday, April 11, 2012

Sviatoslav Richter: Liszt; Schubert, 1958

Today's post marks a rare two week classical streak and part two of this blog's Sviatoslav Richter series with a focus on the man himself. The music on this album, especially Liszt's pieces, are exceptionally good. If you're impressed by the sample, you won't be disappointed by his other compositions here. Richter was one of the great pianists of the 20th century and as was made clear by the critical response to the last album of Richter's that I posted, he had a penchant for redefining classics and recorded famous versions of countless songs. This record captures Richter live in Sofia on February 25th, 1958. Apparently the Doremi label released a CD of one of his concerts from about two weeks earlier in Budapest that features some of the same pieces as this album.

Like the last Richter album that I posted, this one is unmistakably live: instead of the recording quality being rough and the air conditioning possibly being on, an audience member sneezes a couple of times on side A. This Columbia disc is presumably one of the recordings that primed American audiences for Richter's 1960 visit to Carnegie Hall. One side is dedicated to Liszt and the other to Schubert. On Liszt's side are Harmonies de Soir from Etudes d'exécution transcendante, No 11 in D-flat Major, Feux Follets from d'exécution transcendante, No 5 in B-flat Major, Valse Oubliée No 1 in F-sharp Major, and Valse Oubliée No 2 in A-flat Major. On Schubert's side are Moment Musical in C Major, Op. 90, No 1, Impromptu in E-flat Major, Op 90, No 2, and Impromptu in A-flat Major, Op 90, No 4. I think Igor B. Maslowski's biography of Richter on the back of the record is insightful because it describes Richter as both a highly gifted artist and an eccentric character, two traits that often go together. Here it is it's complete form:

"Sviatoslav Teofilevitch Richter was born forty years ago at Zhitomir, in the Ukraine. German-Russian by descent ('with a dash of Tartar Blood,' says he with a smile,) he is a blond giant with a striking build and fantastic hands (he has an octave reach between his index finger and his little finger.)

His father, a composer and pianist, never intended to have "Slava" become a musician; his mother, however, thought otherwise, and so she sent her son to Odessa where he studied conducting. (Gifted with a prodigious musical memory, Richter is also able to read the most complex scores at sight.) But after three years the young artist realized that he was not cut out for a conductor's career. Then some friends suggested that he might become a pianist, and he went to Moscow to consult with Professor Heinrich Neuhaus. Professor Neuhaus took his as a pupil, and four years later Richter performed Prokofiev's Sixth Sonata. This was to mark the beginning of a close friendship between him and the composer, a friendship which lasted until the death of the latter.

Right from the start Richter was hailed as a prodigy and each concert has has given since then has been an event of the first order.

Richter is an unusual person. Some say he is difficult, others insist he is charming. The fact of the matter is that we must distinguish between Richter as an artist and Richter as a man. As an artist he is terribly strict, with himself and with others; as a man he is as pleasant, affable and obliging as can be. A very modest man, he is never quite satisfied with his concerts or recitals, and insists that there is always room for improvement. In his opinion he has only once played really well, and he loves to tell the following anecdote to his friends:

'It was at Gorki, I think': (yes, 'I think' are Richter's own words--his absent-mindedness is legendary, and he is at times unable to remember his address or telephone number, much less the cities he has played in,) 'and they had introduced me as 'Sviatoslav Richter, from the Moscow Conservatory.' As soon as I stepped out before the audience I felt that they were disappointed. But I played well, really well, I was quite satisfied with myself and got ready to do an encore. I never got a chance to, though, as the last piece on the program was greeted only by a polite applause, and I went off, somewhat surprised. I later learned that the audience expected to hear a Professor from the Conservatory--stooped, bearded, monocled, etc. When they saw a twenty-year-old on stage they concluded a priori that he couldn't give a good recital.'

Richter lives in Moscow with his wife, Nina Dorliak, the famous singer; he is her regular accompanist. He likes getting up late, loves works of art, and his favorite pastime is getting his musician friends together. He dislikes being disturbed by the telephone, and hates airplanes, which he takes only when he is absolutely forced to.

When he is asked why he never plays in the West, he replies: 'There are still so many Russian cities I've never played in.'"

Wednesday, April 4, 2012

Janos Starker: Dohnányi: Cello Concerto, Op. 12; Kodály: Sonata for Solo Cello, Op. 8, 1958

Janos Starker is a Hungarian Jewish cellist of Polish and Ukranian descent who has lived in the U.S. since the late 40's. He teaches at Indiana University's Jacob School of Music and apparently still performs on rare occasions. He played cello from a young age and according to wikipedia had five regular students of his own by the time he was 12. His technical ability is astounding, but what makes him an amazing musician is the finesse, control, and care that define every second of these performances. With Starker's help and that of a few others, I'm starting to understand how a performer can shape a piece by interpreting it on a level that exceeds the artistic vision of normal musicians. As Starker brings out the beauty in the works of these composers, we hear a melding of great musical minds; it is truly a collaborative process even though these works were written decades before this performance, before Starker was even born.

The sonically rich A side features Starker playing over the Philharmonia Orchestra (of London) conducted by Walter Süsskind. Kodály's piece, in spite of its modest instrumentation, is intense and energetic and covers a surprising amount of ground. The liner notes give an interesting account of Kodály. As author Frank Hampson put it, his music "scratches the surface" of the Eastern European folk music that inspires it while Béla Bartok's "dug deep" in this regard. (Incidentally, the two men were friends and made some expeditions to collect folk songs together.) Hampson is careful to point out that Kodály's pieces are equally informed by a deep understanding of and respect for folk music, it's just that his approach grafts folk themes "onto a fundamentally French Impressionist background." He touts Kodály's music as genuinely Hungarian and deeply personal. Kodály's compositional practices indicate an awareness of the then-current European notion that the soul of the people resides in an endangered body of folklore kept alive in mostly marginalized corners of the countryside where progress has yet to pave over the nation's quaint traditions. Still, I can't help but read his fusion of this music with a distinctly modern style (not to suggest that Bartok was any kind of purist) as a nod to the fact that he was living in a world much bigger than his own country. His time studying music in other parts of Europe, notably France, must have made him aware of this. Kodály's music acknowledges that the though he desires to rediscover his roots through folk forms, he and most of his listeners were born a ways away from these folk roots, and musical forms from other parts of the world may be just as relevant to them as homeland varieties. I imagine that Starker, whose background was even more international than Kodály's, must have appreciated these elements in Kodály's work, although I'm not well enough acquainted with Hungarian folk music myself to recognize its influence on this sonata.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)